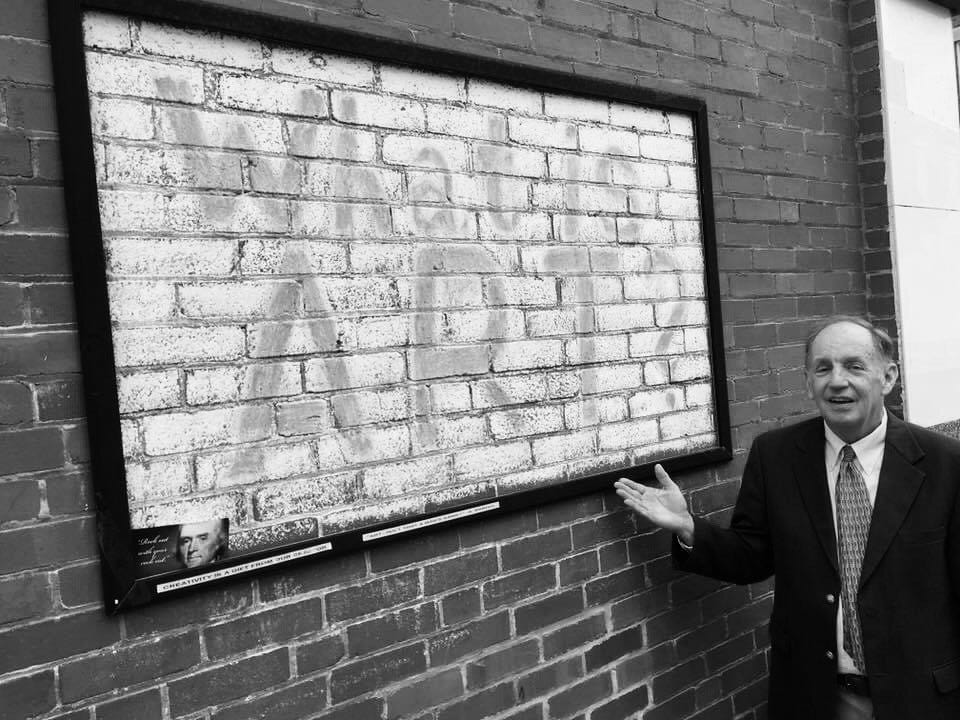

“What is Art?” asks a chalk message on Staunton, Virginia’s New Street. “Here is the wall, I am the fly!” — Photo by Janae Fair

What is Art?

I was recently a “fly on the wall” overhearing a discussion of just that question. It surely is not a new question for me. We seem to always touch on the subject in discussions with our students, and it is certainly a place where there is plenty of discussion — and plenty of diverse opinions! Most often, it seems one will tell you what ISN’T art. It often appears rooted in subjective observation and personal taste.

Some will opine that art is a high form, instructed by technique and a set of rules. We certainly teach technique and I would not argue that there is a body of historical work that must be considered as a basis for the study of art. In fact, few would say the Renaissance masters were NOT artists. The discussion becomes far more interesting as we consider more modern periods.

The Hudson River School painters were brilliant. Today we love their work. Frederic Edwin Church is universally admired. But there was a time when the work of these great landscape painters fell out of favor. A sort of Romantic Classicism came into vogue. The works were beautifully executed paintings of mythology. They were good paintings, but lacked the original response to majesty found in the Hudson River School.

Today we remember the landscape masters — not so much the later romantics. We also tend to forget that many of the great artists of the nineteenth century were also engravers — read that they were part of the publishing process. Thomas Cole, the father of the Hudson River School, began as an engraver. Publishing technology developed greatly towards the end of the nineteenth century. Four color process allowed for the reproduction of magnificent paintings.

Howard Pyle [click to read] was one of the first artists to transition into the new reproduction methods. He painted rich oil compositions on large canvases that were photographed through a series of color filters — to become illustrations in books. He taught Newell Converse Wyeth [click to read] his exacting technique. Wyeth painted beautiful large canvasses that were destined to become book illustrations. They are masterworks that even when reduced seem to jump off of the page.

But N. C.Wyeth often painted over these magnificent works once they had been photographed. His son, Andrew Wyeth, was taught by his father and enjoyed an incredible career as a fine artist. Yet Newell Wyeth was always bothered by the fact that he was known as an “illustrator.” The term was seen by some as a pejorative. N. C. Wyeth often turned his illustrations into the base for landscapes and such.

When conservator Joyce Hill Stoner asked Andrew why an artist would paint over a canvas, he responded with the typical reasons — it saves stretching a new canvas, it saves money. Andrew then became livid; “my father had PLENTY of money!” Andrew said his father always seemed to struggle with this. Though illustrators really had their own culture, their own networks, and their own place, the “established” art intelligentsia looked down on them.

Yet the Wyeth family, Howard Pyle, and Norman Rockwell, who was inspired by Pyle, have created an incredible body of work. In my mind, it is art.

The Academy Digresses

Meanwhile, one does not have to look far to see that the art intelligentsia themselves have walked away from a more traditional definition of art. Marcel Duchamp’s “Fountain,” originally a protest of the academy’s preoccupation with technique, became the “Readymade” movement. ANYTHING could be art. Michael Craig Martin can call a glass of water “An Oak Tree.” Art, it would seem, is robbed of its objective portrayal of the beautiful.

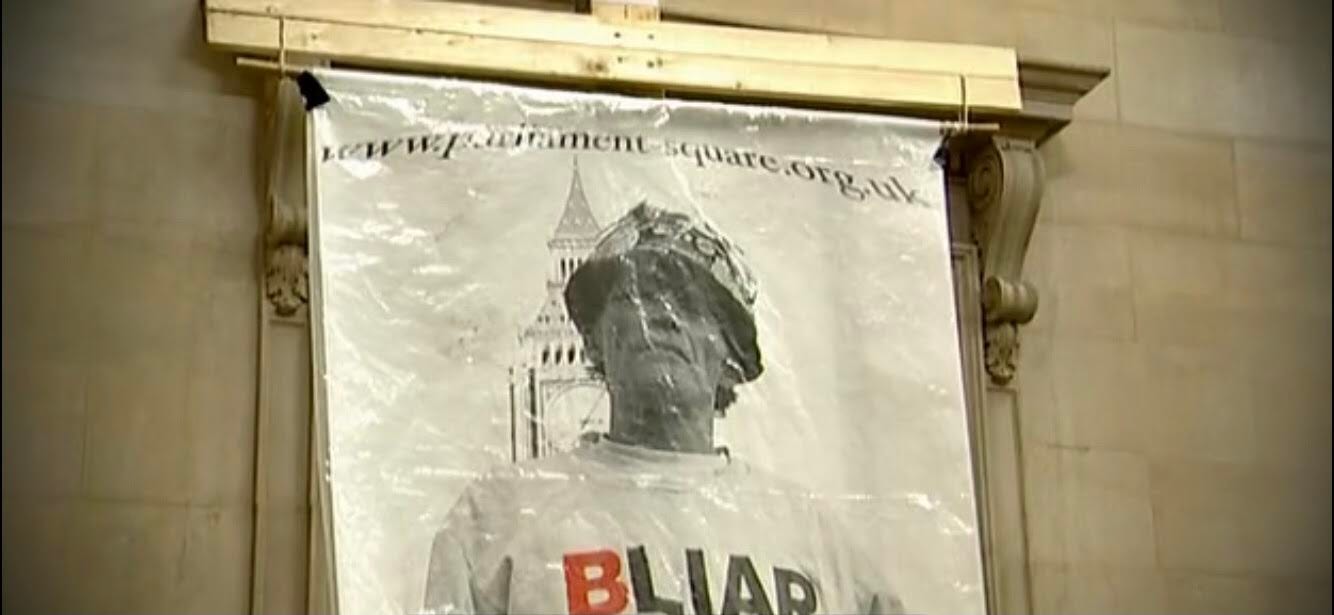

While the illustrators of the nineteenth century elevated art and its purpose, modern movements have degraded it to portrayal and protest. Here we see ‘art’ that simply paints large yellow block letters on a street and calls it a mural. Making a former Prime Minister’s name into block letters and finding LIAR in BLAIR, is that art?

Roger Scruton [click to read] would say not. His documentary is well worth watching, and should be part of the discussion. But so far it seems we have perhaps defined some things that we might think should not be considered art, but have we defined it? There is always a point in my study of something that drives me to the dictionary and the encyclopedia. So now, here is a more structured look at art’s definition.

A Formal Definition

art /ärt/

Noun

The conscious use of the imagination in the production of objects intended to be contemplated or appreciated as beautiful, as in the arrangement of forms, sounds, or words.

Such activity in the visual or plastic arts. "takes classes in art at the college."

Products of this activity; imaginative works considered as a group. "art on display in the lobby."

— The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, 5th Edition

Britannica says: “art, a visual object or experience consciously created through an expression of skill or imagination.”

The Intersection of Skill and Imagination

From the formal definition it may be reasoned that art is essentially a human act involving skill and imagination. The constructions of animals (bees, bowerbirds, beavers, Baltimore Orioles, etc.) are driven by instinct, and not necessarily imagined designs. There is certainly design present in these creature works, but the creature in this case is not the designer.

The concept of IMAGO DEI (that man is created in the image of Creator), carries with it the idea that imagination and creativity are attributes of the Divine, and part of the imparting of the Divine Image.

EX NIHILO Creation is another concept that underscores creativity as something uniquely residing in the Divine —Something imparted to the human artist.

The Place of Inspiration

“And the Lord spake unto Moses, saying,

See, I have called by name Bezaleel the son of Uri, the son of Hur, of the tribe of Judah:

And I have filled him with the spirit of God, in wisdom, and in understanding, and in knowledge, and in all manner of workmanship,

To devise cunning works, to work in gold, and in silver, and in brass,

And in cutting of stones, to set them, and in carving of timber, to work in all manner of workmanship.

And I, behold, I have given with him Aholiab, the son of Ahisamach, of the tribe of Dan: and in the hearts of all that are wise hearted I have put wisdom, that they may make all that I have commanded thee;” — Exodus 31:1-6

Thus a traditional understanding of art and its definition would allow for inspiration. It would allow for the human portrayal of truth, both observed and transcendent. It would not outright deny the existence of objective truth, the conundrum being that if you absolutely deny the existence of absolute truth, you are essentially STATING an absolute truth.

The Place of Observation

If there are absolute truths to be observed, the artist must become an astute observer. Leonardo [click to read] studied the wonders of nature with a passion. Baroque sculptor Gian Lorenzo Bernini studied human anatomy. He was just twenty three when he executed the sculpture shown here.

The Abduction of Proserpina (1622) — Gian Lorenzo Bernini

In the Renaissance period, it must be noted that art was considered more of a trade, and was largely taught by apprenticeship. Artists such as Leonardo also designed buildings, military weapons, and were party planners as well. Yes, they staged elaborate balls for their royal masters. Some of Leonardo’s flying machines may indeed have been concepts developed for stage decorations.

The Place of Mission

Art initially carried with it a purpose to convey great truths through the portrayal of beauty. It did not gloss over the harsh reality of the world, but rather used beauty as a platform to speak into it. That is why one must not be too quick to dismiss the BLAIR protestors. Though they lack many of the characteristics traditionally associated with great artists, they nonetheless respond to their perception of the world.

Perhaps art is best served then by acknowledging its wide history. I can agree with Scruton that there is indeed a body of superior art, I can also agree with Dennis Raverty [click to read] when he laments the art intelligentsia’s snobbery toward illustrators. Art can (and should be) a big tent. Not all art will necessarily carry the same value, but that should add to the richness of our exploration of it.

Renaissance Paragone: Painting and Sculpture

[click to read]

In an art-historical context, the Italian word paragone (“comparison”, pl. paragoni) can refer to any of a number of theoretical discussions that informed the development of artistic theory in 16th-century Italy. These include the comparison between the differing aesthetic qualities of central Italian and Venetian schools of painting (the so-called disegno/colore paragone) and whether painting or literature was the more convincing and descriptive medium. But the term paragone most often refers to debate about the relative merits of painting and sculpture during the Renaissance period. This debate unfolded primarily in Italy but also in the Low Countries (Flanders and the Netherlands) in writings about art and artworks themselves, and informs our understanding of some of the most significant art and artists of the Renaissance. (read more)

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes

Charles IV of Spain and His Family is an oil-on-canvas group portrait painting by the Spanish artist Francisco Goya. He began work on the painting in 1800, shortly after he became First Chamber Painter to the royal family, and completed it in the summer of 1801.

My art history professor, Penny Griffith, had a great lecture on this painting. Francisco Goya, as court painter, creates a brutally honest appraisal of the Spanish Royals. Charles IV is off center in the composition — “a man who seems more concerned with his hunting dogs than with the affairs of state!” according to Griffith who goes on to point out that Maria Luisa of Parma, the queen mother, is positioned centrally and dominates the composition. This is a scathing portrait of her true influence over the Spanish rule.

In the background, left, is Francisco Goya himself at an easel. “If Charles IV of Spain and His Family were a fable, it would be, without a doubt, The Emperor’s New Clothes. This is the story of a king so vain that he doesn’t realize he’s been made the butt of a terrible joke by two trickster tailors.” states Hypercritic. One has to wonder how Goya got away with this brutally honest caricature of the royals, given it was done in their employment!

This is a great example of art using beauty as a vehicle to convey truth — and perhaps protest the serious problems in nineteenth century Spain. Also, one might observe that the artist was quite literally risking his neck in creating this work.

Block Letter “Art”

The modern era has seen artists continue with a sense of mission, but perhaps an outright abandonment of technique. Are the following examples art… or signs? And can a sign be art?

A protest of the Prime Minister cleverly finds a word in his name.

Here block letters on a street protest police violence — but their ‘vandalism’ by people concerned about the harm ‘defund the police’ will do to their communities creates a composition in its own right.

Visualisation du plan Voisin pour Paris de Le Corbusier

Visualisation du plan Voisin pour Paris de Le Corbusier

Chapel at Ronchamp — Le Corbusier

Though the Brutalist architects did create some beautiful buildings, one is thankful that Le Corbusier did not ‘remake’ Paris! [1.] Roger Scruton looks at an abandoned modernist city centre and sees that like Soviet era mikrorayons, [2.] it lacks a human-scaled environment. It has been abandoned because “nobody wants to be there. Nobody wants to be there because it’s so (expletive) ugly!”

It is covered with graffiti — abandoned to the vandals. But Scruton asks if the architects themselves are not the vandals? It is they who have created this void. The vandals have merely arrived to fill it.

Thus Scruton observes that the ‘art’ itself may not be as significant itself as is the reaction to it — at least in modernism.

Art Worth Dying For?

This past weekend a student asked a profound question; “Is saving art worth lives?” That question begs a continuation of this discussion. “Why,” she asks, “is rescuing great cultural achievements from destruction or theft worth risking one’s life?” Clearly that presupposes that there are indeed works of art that are of such significance that their preservation is worth great risk. Totalitarian regimes do indeed make great efforts to obliterate the narrative of great works. Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 and Orwell’s dystopian novels speak of standing in the face of this. Jules Verne’s Paris in the Twentieth Century [click to read] creates a similar dystopia where it can be observed:

Verne’s vision of a modern Paris in 1960 indeed predicts skyscrapers and technology that came to be, but it is even more amazing to note that Verne’s dystopia predicts a future world where the great art, literature and music – the rich fruits of centuries of Western culture – have been all but forgotten! Instead, the culture of the day celebrates technology and commerce. ‘Old’ things have nothing to say to us anymore! The hero of the story, young Michel Dufrénoy, goes into a modern bookstore and asks if they have anything by Victor Hugo. The clerk responds by asking “what did he write?”

Jules Verne predicts most damningly our society’s modern intoxication with ugliness. Go to any modern art school or venue and you find more of a cold mechanical sort of art aimed more at‘expression.’ Roger Scruton has written on this phenomenon and how the great works of the past have been pushed aside. Scruton opines: “The current habit of desecrating beauty suggests that people are as aware as they ever were of the presence of sacred things. Desecration is a kind of defense against the sacred, an attempt to destroy its claims. In the presence of sacred things, our lives are judged, and to escape that judgment, we destroy the thing that seems to accuse us.”

Thus Michel and his friends, artists of the‘old’school, are faced with the challenge of preserving the old and instructive culture in the face of a modern world that distains it. Verne’s work finds itself specifically troubling in its prediction of modern society’s distaste for a past that would inform it! And so, much like Dufrénoy’s friend and colleague Quinsonnas, we find ourselves as artists frustrated by the modern culture. We long, as he did to somehow ‘astound the age!’

And so I leave you with Astound the Age [click to read], which is meant to be a continuation of Verne’s novel, much as he created From the Earth to the Moon and Round the Moon as a two volume set. Perhaps he would have done so himself had not Hetzel rejected the first book.