A New Francis Scott Key Bridge — Sir Norman Foster

“What if?…” I ask, as the epic failure of the Francis Scott Key Bridge continues to play endlessly on the media. “What if we actually start thinking of doing something better?” I think we have all seen the weakness of a truss design on relatively unsubstantial columns.

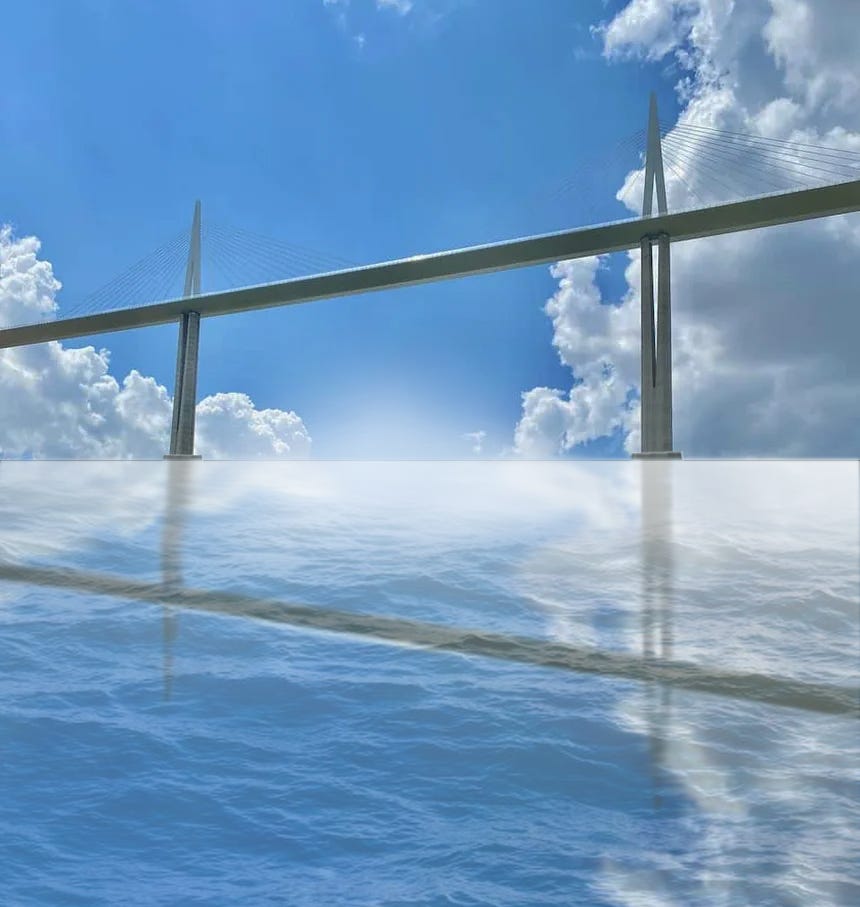

But enough is enough. “Bring on the Visionaries!” Here is Norman Foster’s Millau Viaduct reimagined as a span over the Patapsco River entrance to Baltimore Harbor. Why do I love the Millau Viaduct? Why do I love Foster’s amazing design for it?

First of all, Foster is a modern designer who still has one hand in the craftsmanship of older times. The cable stayed bridge itself is not as new as we might think. John, Wasington, and Emily Roebling actually incorporated a cable stayed design into that of the Brooklyn Bridge — as a backup to their suspension bridge.

It took a family to build that bridge. John, who designed it, stubbornly refused to see a doctor when his foot was crushed — ironically by the ferry his bridge would one day replace! He died from the resulting infection.

But Redundancy was resident in the Roebling family. Son, Washington Augustus Roebling, took up his father’s work. He nearly died from Caisson Disease, or The Bends. Emily Roebling took up the task of finishing the great bridge her father in law and husband had originally conceived. [1.]

For years suspension bridges were representative of the high art of bridge building. In the nineteenth century Isambard Kingdom Brunel [ 2.] built a fine example across the Clifton Gorge in Bristol. His design was suspended from twin catenaries consisting of iron chains. Though Roebling and others moved to spun cables, the old chain design remained in use.

The Silver Bridge across the Ohio River was such a bridge. Sadly, the links themselves had no redundancy should one fail. A failure of one of the links sent the Silver Bridge plunging into the river with many lives lost.

Of late, many fine bridges have been built that are cable stayed. They are redundant by their very nature. They are also quite beautiful — especially when they spring from a mind like Foster’s.

Foster began designing the piers for the Millau Viaduct with hand sketches. Yes, they were later modeled in computer, and later modeled by hand for wind tunnel testing. The point is that Foster began with REAL intelligence, not the artificial kind.

He obviously wanted to understand the forces that would come against his bridge, like wind, and drawing gave him a unique mastery of his project. His approach would be a welcome one, should he be asked to take up the rebuilding of the Francis Scott Key Bridge.

The Millau Viaduct —Sir Norman Foster

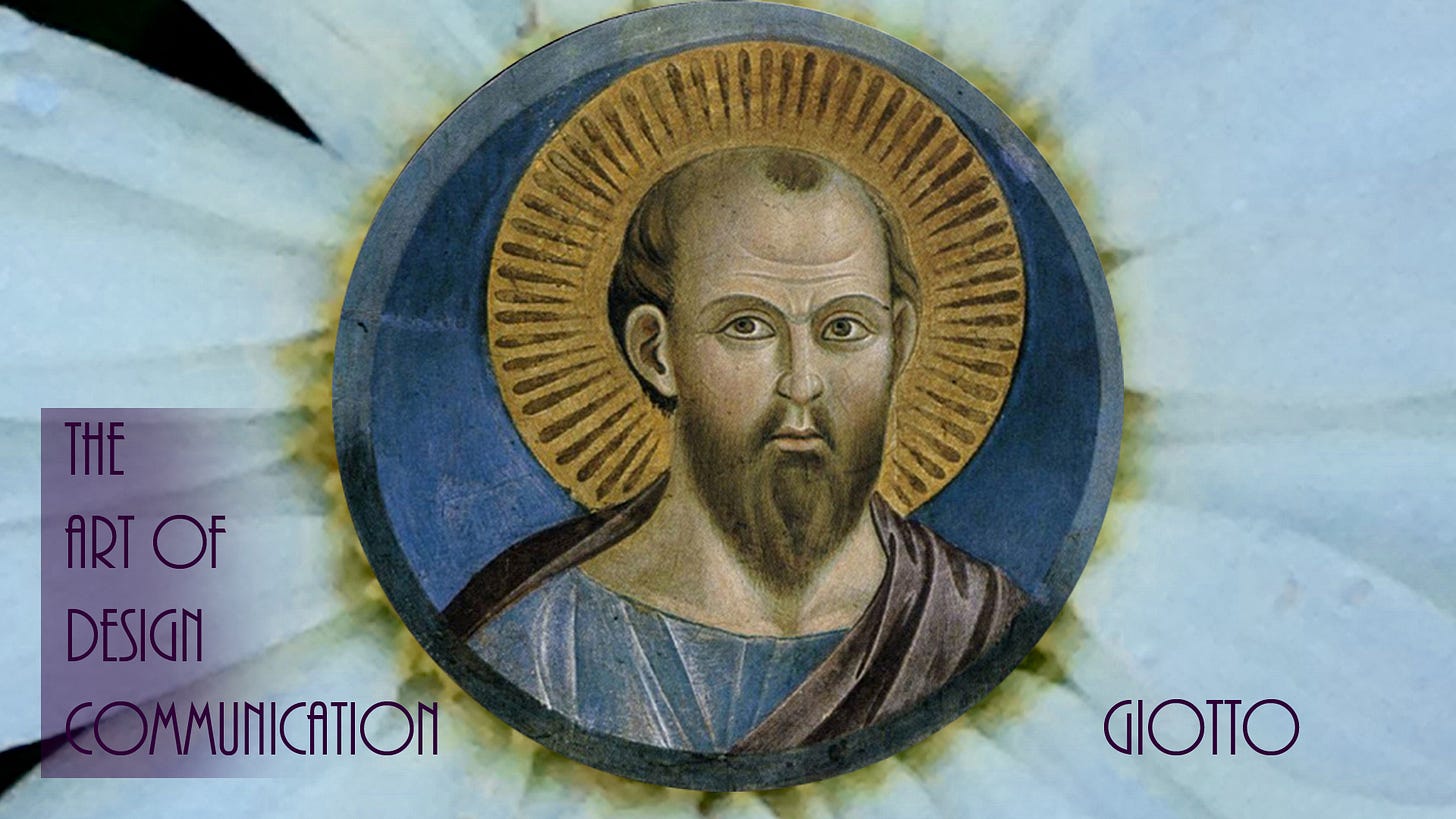

Giotto’s ‘Perfect’ Circle

[click to read]

When Pope Benedict XI desired some frescoes for the great St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, he sent his courtier to search out the perfect artist for this important project. Arriving in Florence, the courtier made his way to the studio of Giotto di Bondone (circa 1267–1337). The courtier explained his mission and asked the artist for a sample of his work.

According to the story, Giotto took a small canvas, dipped his brush in red paint, and holding his elbow tight to his side like a compass, quickly dashed off a perfect circle. “Here’s your drawing” he said, handing the courtier the canvas. The courtier thought he was being mocked, but Giotto insisted, “Surely this is enough, and more than enough!” The man was perturbed, but he took the rendered circle back to the pope and presented it along with the samples of all the other masters. (read more)

Thank you to Claire Venus for the challenge to better writing on Substack!