In 1931, the International Harvester Company commissioned N. C. Wyeth to paint this illustration of the first public demonstration of the McCormick Reaper in Steele’s Tavern, Virginia. There is a copy of this painting at the Cyrus McCormick Historical Site in Steele’s Tavern.

The Great Reaper War

Virginia history tells us of Cyrus McCormick and his invention of the reaper. It is a fascinating story, but there is a bit more than is often told. In fact, Cyrus most likely didn’t invent the first mechanical harvesting device. There were others working on such a machine at the same time. In fact, McCormick wasn’t alone in patenting and selling them. Before McCormick Harvester could become International Harvester it first had to win the “War of the Reapers.” It was a great battle to be sure – and it didn’t even take place on American soil! It happened in the English countryside.

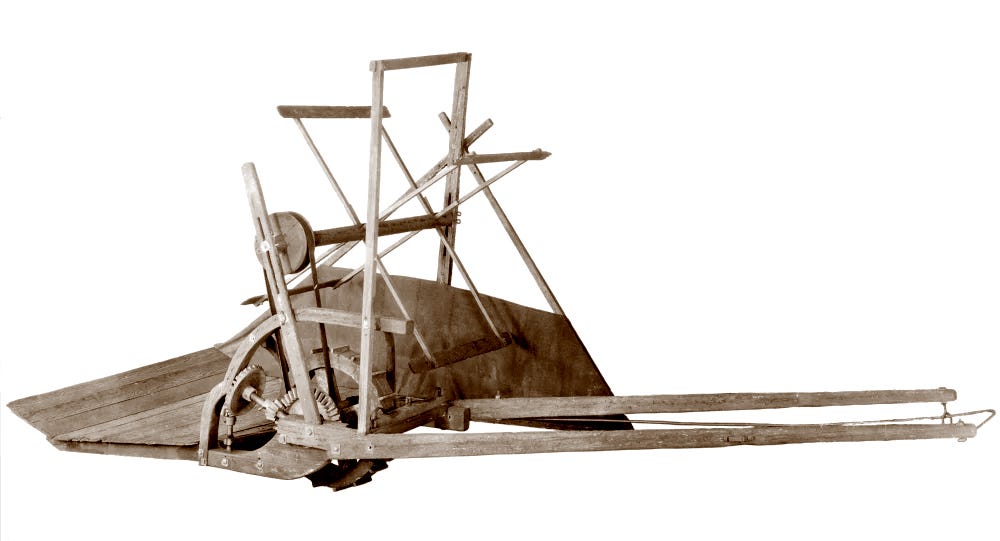

The McCormick Reaper — Historical Photograph

It all started in 1849 when Englishman Henry Cole convinced Prince Albert, the husband of Queen Victoria, to hold what would be the first-ever World’s Fair. The two men became friends because of their mutual membership in the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce. Cole told Albert that such an international exhibition would “educate the public and inspire British designers and manufacturers.” Britain at the time considered itself the innovative hub of the world. The country was indeed building great bridges, tunnels, and railroads, all financed by her booming overseas trade. This was bolstered by considerable colonial holdings – such as tea, sugar, cotton, and opium – which all fed the engine of the Victorian superpower.

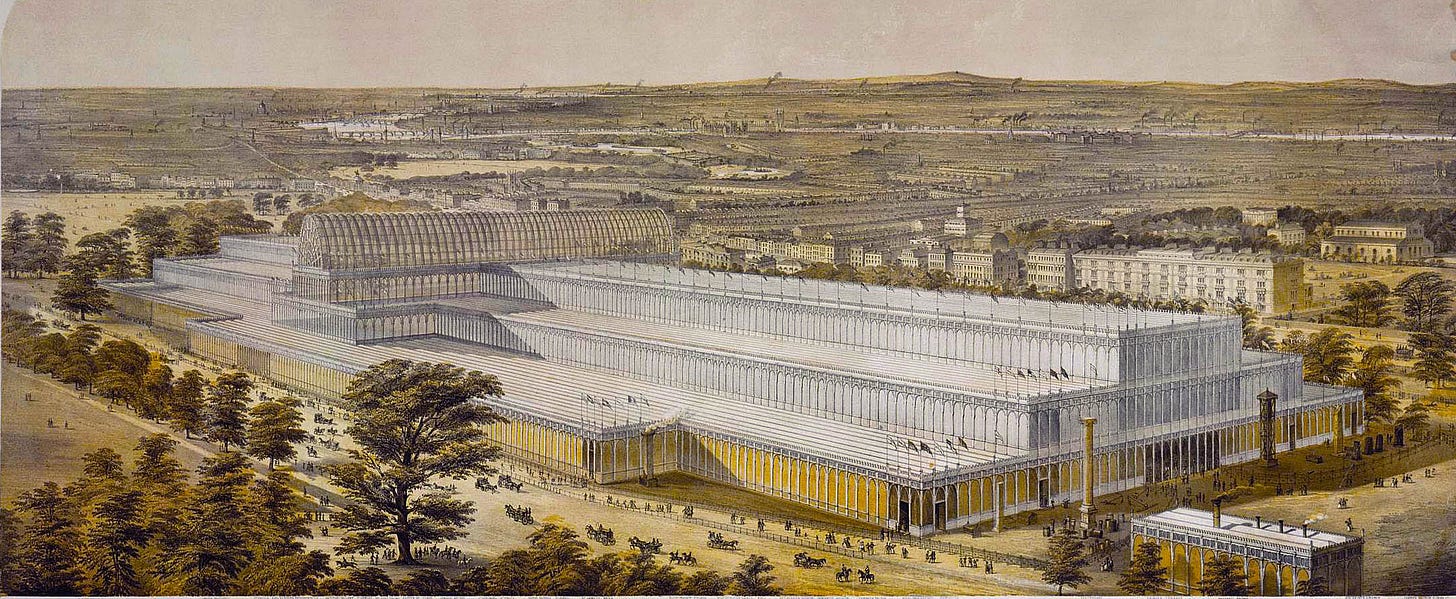

Cole and Prince Albert decided to build the world’s largest building to house the exhibition. There was an open design competition which attracted 245 entries; however, the commission didn’t like any of them! They instead sought out four architectural experts who came up with a massive building. Unfortunately, it would be impossible to build this huge structure in time for the exposition’s opening in May of 1851. In a foreshadowing of things to come, it would be an agricultural expert who would come up with a solution.

Coming Late to the Fair

The fair’s required massive venue was made possible by an entry made way past the deadline by Joseph Paxton. At the age 14 he had left school to become an apprentice gardener. By the age of 22 he had become the head gardener at Chatsworth, one of England’s finest gardens. Here the young man began building greenhouses. In fact, he built a greenhouse at Chatsworth that was so big Queen Victoria toured its interior in her carriage. This building inspired his design for the 1,851 foot long “Crystal Palace.” The length of the building was intentional. By using new methods of prefabricated construction and a newly invented large pane plate glass, Paxton was able to deliver the largest building in the world in time for the exhibition. This huge building was one enormous greenhouse. Exhibits lined the open space that ran the length of the building, and another perpendicular row that bisected it in the center. Some stately elm trees on the site were simply incorporated into the brightly lit interior space.

Paxton had not received a warm welcome from the fair commission, so he went around them, publishing his idea in the Illustrated London News. In the end, it was the only building that could be built by the deadline. The project was completed in just eight months. The western half of the building was reserved for exhibits from Great Britain, and the eastern half was for exhibits from all the other countries in the world. No one expected much from the Americans. English troops had burned their “wilderness capital” just 37 years prior. They had, as a courtesy, spared the American Patent Office, but no one expected anything world-changing to come from the former colony.

The Americans Show Up Late as Well

The exhibits from America were among the last to arrive at the fair. They did not seem to represent a technological powerhouse, but the British were about to see a demonstration of American innovation and competition they would not soon forget. As the American exhibitors uncrated prototype sewing machines, the Colt Revolver, new designs in dentures, and innovative farm equipment – people took notice. America was indeed an incubator of innovation, and the exhibits were fascinating to see. Later that summer two of them would be put to the test in a demonstration that would change farming around the world.

Cyrus McCormick’s reaper was there, but so was one made by Obed Hussey of Baltimore. It seems that while McCormick was perfecting his father Robert’s idea for a harvesting machine, the Maine-born Hussey was working on a harvester as well. Apparently the two men had no idea there was someone else trying to build a reaper. Hussey actually patented his machine first. They were not the only ones vying to create a workable reaping machine. The British Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce had even offered a prize for the development of just such a device.

A Scottish minister named Patrick Bell had in fact built a reaper. It did not work very well and had been largely abandoned by farmers, though some of the Bell machines had been sold in America. Its design differed from the rotary driven, toothed cutter bar technology exhibited by McCormick and Hussey. Even so, some observers claimed the Americans had ‘stolen’ the idea from Bell. Hussey worked quite independently. Cyrus McCormick actually took up a reaper project that his father Robert had begun. The elder McCormick never felt that he had created a machine that would work satisfactorily. His son made some changes to the machine, which he demonstrated to an eager crowd in Steele’s Tavern, Virginia, in July of 1831.

Competition and Improvement

In the years preceding 1851, the Hussey reaper was actually considered by many to be a better machine. The two inventors sparred for dominance in the farm equipment market. Hussey gained market share in the northeast, and McCormick went west to the frontier town of Chicago. There, railroads offered new markets and the land to the west was perfect for growing grain. McCormick poised himself to serve that newly opened market – and unknowingly poised himself for so much more.

A McCormick Reaper in operation.

The Hussey Reaper.

Two men and two machines were ready for the test. Cyrus McCormick was tall and handsome. His rival, Obed Hussey, was a former Nantucket whaler. He looked the part, wearing a black eye patch that made him look a bit like a pirate. He was, in fact, a mild-mannered and somewhat reclusive member of the Society of Friends (Quakers). McCormick was probably the more competitive of the two inventors. The perpetual tinkerer, Cyrus never ceased methodically working to improve his reaper. Both machines remained merely concepts that summer as they sat on the floor of the Crystal Palace. In August of 1851 that all changed. Cyrus McCormick arrived in England for the final trials of the reapers, which was to be an actual harvest. Hussey had traveled on to France, and when the big day came he was not there to supervise his machine’s operation. The McCormick reaper won the day, winning the Grand Council Medal. Ironically, another test was made of the machines when Hussey returned to England. This time, operating under his direct supervision, the Hussey Reaper won.

The judges noted that both were sturdy machines and harvested well. The Hussey, it was observed, was superior at cutting grass. The McCormick excelled at cutting wheat. Hussey continued to sell his reaper, but as the American prairie and overseas markets opened to McCormick, the Virginia inventor built ‘the largest factory in Chicago’ and sold his machines to a waiting world. His company would later become International Harvester – a major provider of farm equipment for decades. Though Hussey came in second in the reaper war, he continued to develop better machines for agriculture. At the time of his death he was working on a design for a steam driven plow.

The Crystal Palace that housed the London World’s Fair. — Public Domain Images