Lincoln Highway, Wendover Cutoff, Great Salt Lake Desert, Knolls, Tooele County, Utah. The last major link in the first transcontinental highway. It’s designers solved problems presented by vast mud and salt flats.— Historic American Engineering Record, LOC

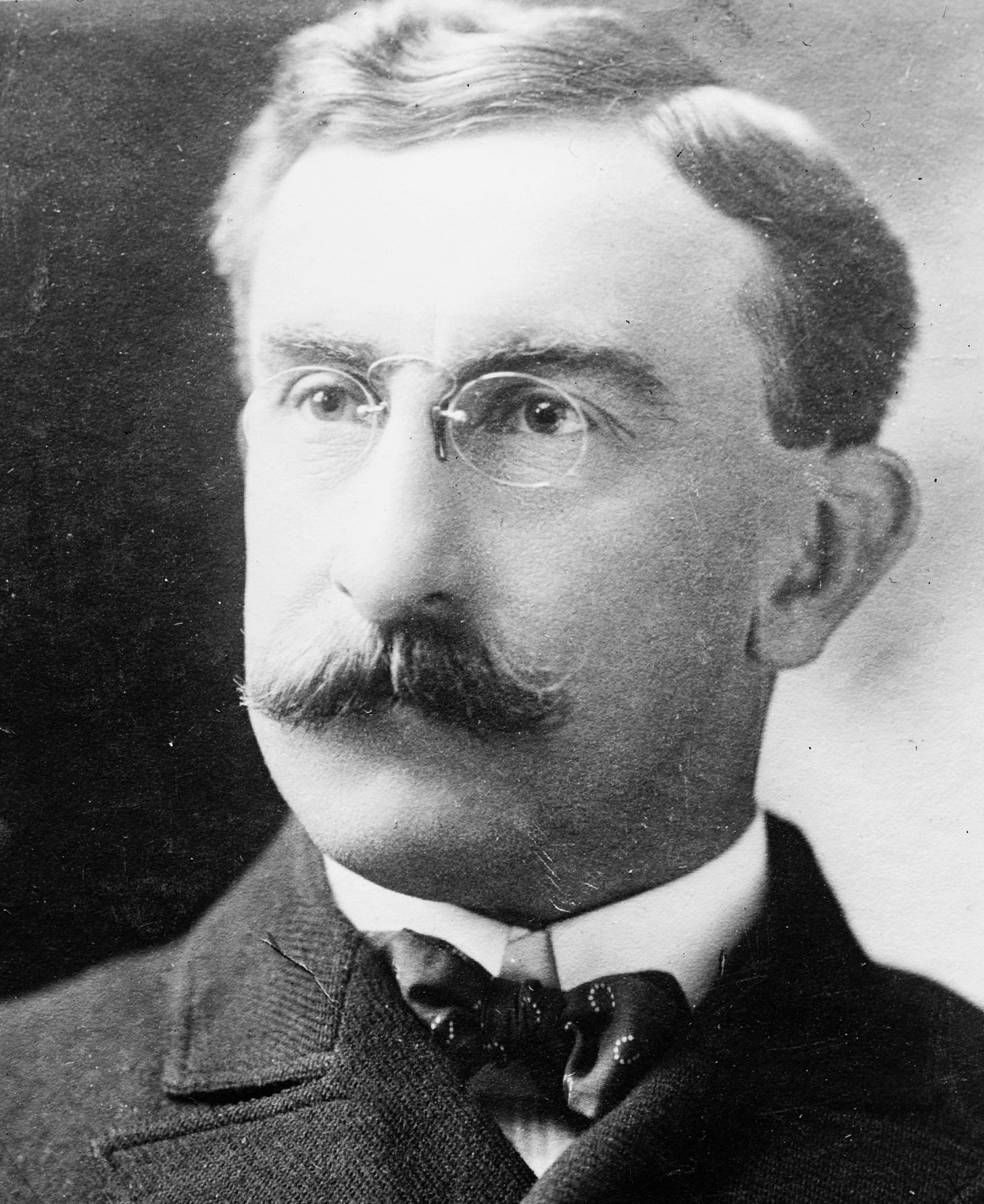

Carl Graham Fisher. — Library of Congress Photo

Lighting the Way for America’s First Coast to Coast Automobile Road

Carl G. Fisher and the Lincoln Highway

Carl Graham Fisher loved bicycles as a young man. He raced them, wrecked them, and repaired them. He even opened a bicycle shop along with his two brothers in 1891. What is amazing about this is that Carl suffered from severe astigmatism, his vision was far from perfect. The headaches, eyestrain, and blurred vision had made school a challenge. At twelve he quit because he had to help support his family. His father had left them.

The bicycle shop came to be after Carl had worked a series of odd jobs. He had earned his diploma from the school of hard knocks. Now he learned about the wonder of embracing emerging technology. In 1904 Fisher partnered with James A. Allison to buy an interest in the United States patent for the manufacture of acetylene headlights. Automobiles themselves were an emerging technology at the time, and for the first decade of their existence, they used acetylene lamps, not electric ones.

For that decade, Fisher and Allison’s company, which came to be known as Prest-O-Lite, held its place as the primary supplier of automobile headlights. When the men sold their company to Union Carbide in 1913, they received nine million dollars for it. Fisher was a master promoter. He is credited by some for having operated the first automobile dealership in the United States – in Indianapolis, Indiana.

But automobiles were still a novelty in those early days of the twentieth century. Costing more than an average person’s salary several times over, they remained a plaything for the very rich. Though hand crafted, they were not all that reliable. Fisher noted that the Europeans were building better cars. He observed auto racing in France and noted that they had better racetracks. Seeing the need to develop the serious testing of automobiles in the United States, he proposed the building of a circular (or oval) track in 1905. He initially wanted it to be three to five miles long.

It ended up being two and a half. His old partner James Allison and several others joined him in creating the Indianapolis Motor Speedway Company in 1909. The track was downsized to allow for larger grandstands, resulting in the famous ‘Brickyard,’ America’s first real hard-surfaced racetrack. The brick surface came about after a series of mishaps were attributed to flaws in the tracks original tar and stone chip surface. The bricks proved to be a smooth surface that wore well and provided adequate traction.

The ‘Good Roads’ Movement

Carl Fisher’s fortunes had begun with bicyclists; and it was bicyclists, not motorists, who began the crusade for better and safer roads. Average people didn’t have cars, but in 1908 that was about to change. Henry Ford’s Model T began production that year. It was a tough, basic machine, built on an assembly line. Introduced at a price of $750.00, it had come down to $260.00 a car in a decade. You could even use it to power machinery on the farm! You could even have it in any color “as long as it was black!”

In 1912 Fisher came up with his really big idea. He wanted to build a road across the entire span of the United States. At the time roads were mostly local routes from outlying areas to railroad stations, remains of old wagon roads, old turnpikes, and all devoid of information signage. Outside of major metropolises, they were dirt or gravel, plagued by mud in rainy seasons and dust in dry.

At a September 10, 1912 dinner meeting with friends, he proposed his transcontinental “Rock Highway.” It would be a graded and improved uniform roadway, graveled or chip and seal surfaced. It would be an all weather road. What’s more, Fisher believed it could be completed in time for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. He told those assembled, “Let’s build it before we’re too old to enjoy it!”

The cost was estimated at ten million dollars – a bargain even when adjusted to today’s dollars. An association was formed with Henry Bourne Joy (President of the Packard Motor Car Company) as president. Fisher served as vice president. The name Lincoln Highway was chosen for the road – a tribute to the man who had labored to join the country together after her bitter civil war.

In less than a month, Fisher’s associates had pledged a million dollars toward the road. Contributors included Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, who loved riding in his Pierce Arrow motorcar simply for the joy of it. Thomas Edison chipped in, thinking it was a brilliant idea. Ironically there was one notable holdout, Henry Ford. The entrepreneur who created the assembly line felt that government should build infrastructure.

Henry Bourne Joy. — Library of Congress Photo

The “Ideal Section”

Dedicated in October of 1913, the Lincoln Highway was little more than the designation of existing unimproved roads – in their unimproved conditions! The route stretched from Times Square in New York all the way to San Francisco. On December 13, 1913, the first ten miles of the road were officially dedicated between Newark and Jersey City, New Jersey.

The Lincoln Highway Association embarked on a “Trail-blazer Tour” in 1913 to finalize the route. It was initially 3,389 miles long, but improvements, new construction of right of way and other improvements would eventually make it 3,139. In 1923 a one and a half mile long “Ideal Section” of the road was built between Dyer and Sherereville, Indiana. It was built on a 100’ right of way with a forty foot wide concrete roadway. It was landscaped, lighted, and provided separated pedestrian walkways.

The ‘Ideal Section’ in Indiana. — Historical Photograph

U. S. Rubber Company teamed up with local and state governments to build the “Ideal Section.” It was a model of what a motor road could be! The Lincoln Highway Association’s 1916 Official Road Guide paints a picture of the reality of travel on most of the road. “Don’t wear new shoes,” the guide warned. You could see America on $5.00 a day, but a coast to coast adventure could take up to a month. Drivers, mired in mud, often had to seek out the kind help of a farmer with a good team of horses.

In the Summer of 1919, Lieutenant Colonel Dwight D. Eisenhower traveled in a cross-country convoy along the route. It took about TWO months. This trip inspired the Federal Highway Act of 1956, which created the Interstate Highway System. Largely replaced by four lane expressways, the Lincoln Highway stubbornly remains part of a major east-west Interstate. It is where politics prevented the direct connection of Interstate 70 to its multiplex with Interstate 76 along the Pennsylvania Turnpike.

This bit of irony involves a modern I 70 expressway out of Baltimore, heading west, coming to a grade intersection with the old Lincoln Highway and turning east, before turning south to join the Turnpike headed west again. It creates traffic jams, overheated radiators, and frayed nerves for drivers. Few of them appreciate this brief encounter with highway history.

After the Lincoln Highway was established, Carl Fisher worked to establish the Dixie Highway from Michigan to Miami, Florida. It was in Florida that Fisher saw the potential for developing the beaches. He invested much of his fortune there. Unfortunately a 1925 hurricane and the great stock market crash wiped out most of his fortune. He died on July 15, 1939, a man of modest means, and was interred in his family mausoleum in Indianapolis. His vision lives on in the nationwide system of uniform and safe highways we enjoy today.

Essex and Hudson Lincoln Highway in Jersey City, New Jersey. — Library of Congress Photo