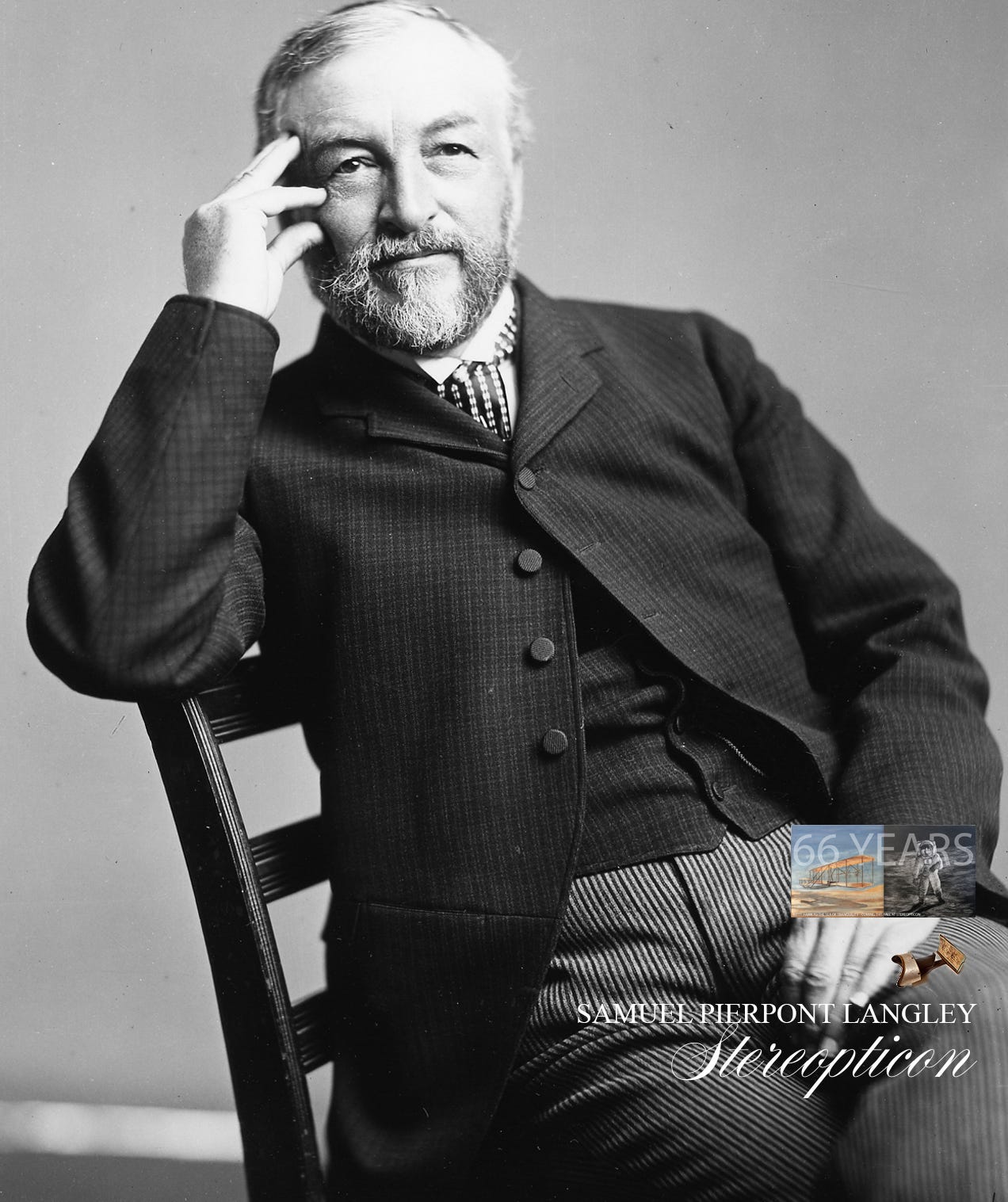

Samuel Pierpont Langley — Public Domain

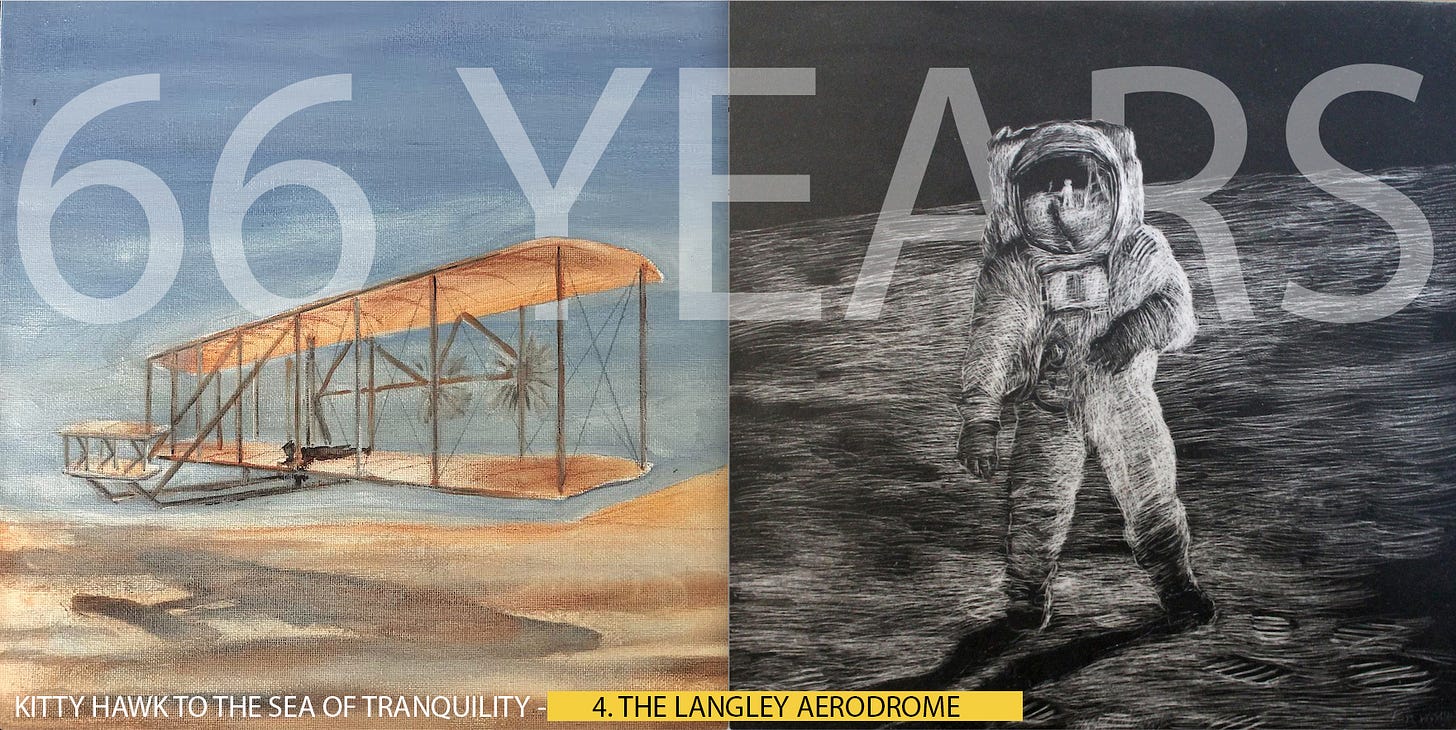

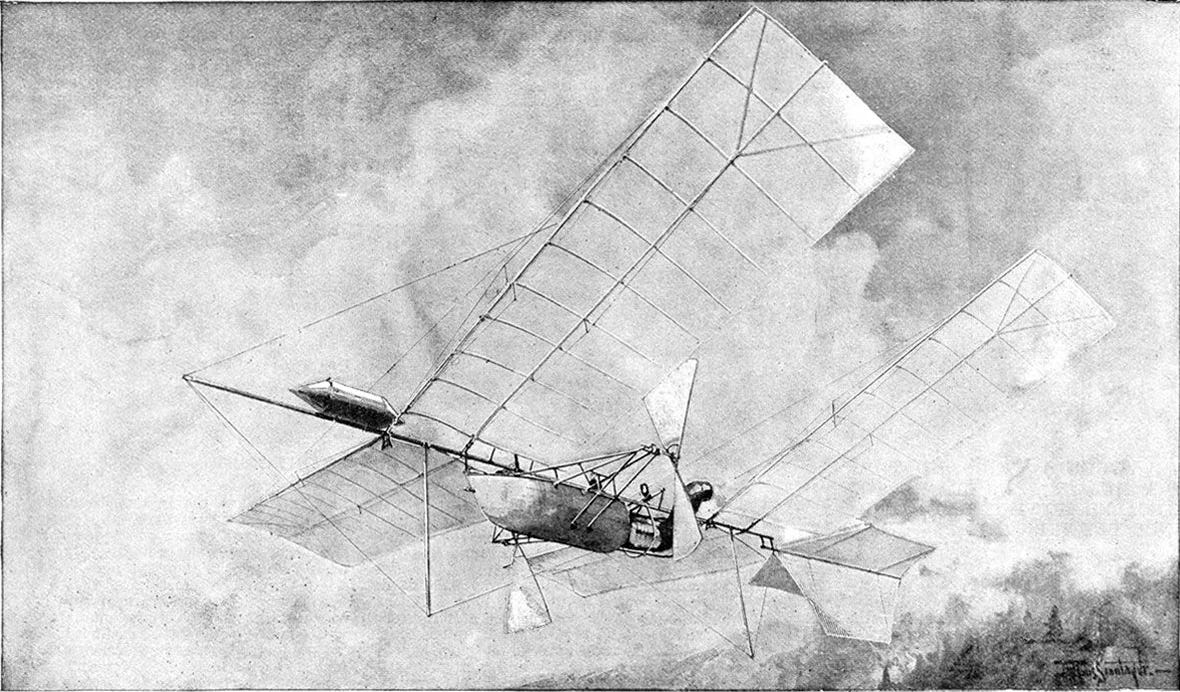

4. THE LANGLEY AERODROME

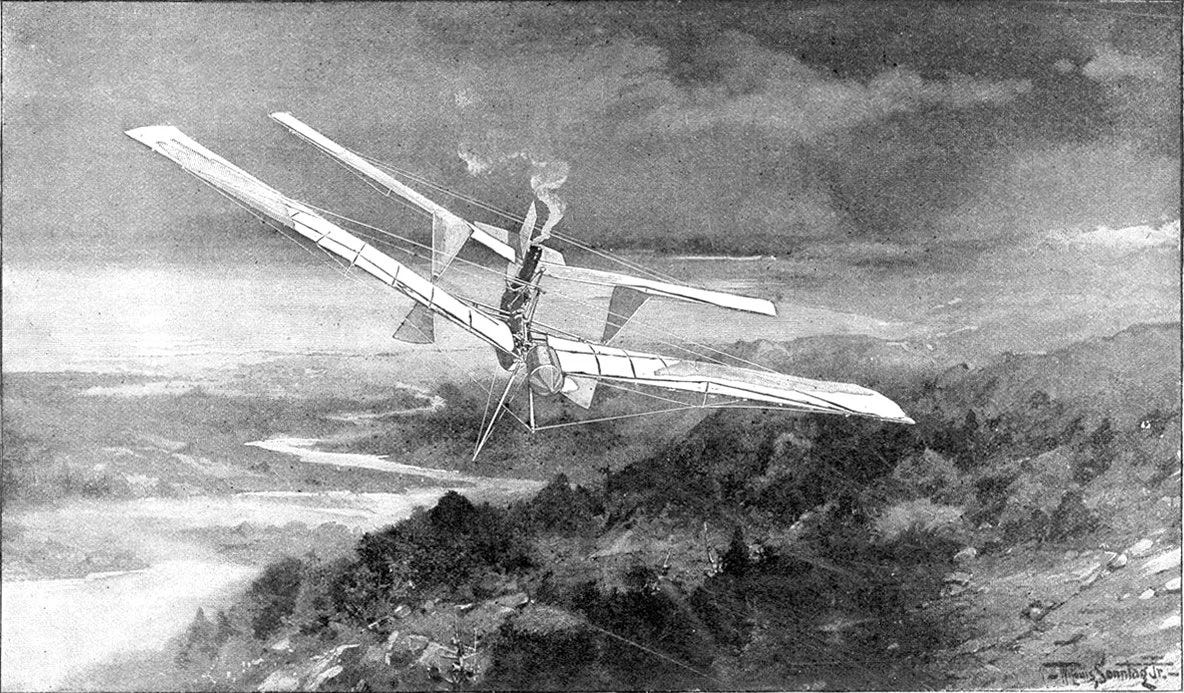

Two drawings on the Langley Aerodrome #6, showing it in mid-flight from below and above. Originally published in The Strand Magazine in 1897. — William L. Sonntag, Jr.

William L. Sonntag, Jr. was the son of William Louis Sonntag (1822-1900), a fine painter of the Hudson River School. The younger Sonntag was probably taught by his father before he enrolled in the National Academy of Design. He became a member of the American Watercolor Society and often painted alongside his father. His true brilliance was seen in his masterful renderings of New York City architecture, ships, and AIRSHIPS, as seen in these beautiful depictions of Samuel Langley’s conceptual airship. Sonntag died young, at the age of twenty-nine, leaving on his desk “several inventions and many plans of useful things.”

Frieze of American History in the United States Capitol, detail The Birth of Aviation depicts Leonardo da Vinci, Samuel Langley, Octave Chanute, and the Wright Brothers. The fresco by Allyn Cox (1953) also contains an eagle with an olive branch…

…predictive of the 1969 Apollo 11 Mission Patch. The Apollo 11 crew was tasked with designing its mission patch, following in the footsteps of the crew of Gemini V. Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins set out to create a patch that would be symbolic rather than explicit, representative of the collective efforts of everyone who had contributed to the mission. The crew decided to keep their names off the patch so that it would include all those who had worked towards the lunar landing. Collins found an eagle in National Geographic and traced it on onionskin for the first sketch, adding a cratered lunar landscape below. At the suggestion of Tom Wilson, who ran the mission simulator, the olive branch was added, unknowingly emulating the art in the Capitol fresco. — NASA

The Langley Aerodrome

In the 1890s, Samuel Pierpont Langley was the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. He was an astronomer and a physicist – and an inventor! In 1886 he began his work with small rubber band powered models. On May 6, 1886, he made two successful flights of his Aerodrome #5. It was catapult launched from a floating platform in the Potomac River – making two successful, but unmanned 700 meter flights.

The initial model weighed 25 pounds and was steam powered. Then Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt secured a $50,000 grant for Langley to develop a piloted model. Langley and his team built a ¼ scale prototype with a gasoline motor. It flew on the 18th of June in 1901. Lessons learned from this flight were incorporated into a second prototype with an improved engine. It flew on August 8, 1903.

Now they were ready to build a full-sized model, capable of carrying a human pilot! It had a 53 horsepower internal combustion engine, but was still fairly primitive as far as controls were concerned. Langley’s chief engineer Charles M. Manly acted as pilot. On October 7, 1903, Manly boarded the craft and it was catapulted from the floating platform.

The aircraft collapsed and fell into the Potomac River. Manly escaped unhurt. The plane was repaired and another flight was attempted on December 8, 1903. Again, Manly was at the controls. Once more the aircraft shuddered and fell into the water. Lengley felt that the problem lay with the launch mechanism and made no more flights with the machine.

Further analysis would show that the catapult mechanism actually put quite a bit of stress on the airframe, seriously damaging it. Furthermore, the controls needed to be perfected. On December 17 Langley’s work would be overshadowed by the Wright Brothers’ flight at Kitty Hawk.

The media was quite unfair in mocking Langley’s failed attempts and published a picture of the craft falling into the Potomac after launch. Langley’s reputation as an aeronautical designer suffered. The Langley Aerodrome never flew again…

…until Glenn Curtiss, around 1909, needed to prove a point. Curtiss had built his own successful airplane but was being sued by the Wright Brothers, who claimed that he had stolen their method of lateral control for an airplane. Curtiss went to the Smithsonian and convinced them to let him reconstruct the Langley Aerodrome.

The Curtiss Reconstruction of the Langley Aerodrome. — Public Domain

Curtiss thought that he could disprove the Wrights’ claim by flying the Langley plane. They took it to the Curtiss factory in Hammondsport, New York and refurbished it. The catapult system was eliminated and the plane was given pontoons. The Aerodrome finally flew on May 28, 1914, lifting off from the water under its own power. As the great war loomed in the future, the government ordered all such court actions dropped, paving the way for aircraft development to proceed. Though the Wrights eventually won a succession of lawsuits, they had arguably slowed critical progress in the development of modern aircraft.

The Wrights pointed out correctly that Curtiss had modified the 1903 Aerodrome, while the Smithsonian argued that the Aerodrome was indeed a flightworthy design, although it required significant refinement. The Aerodrome was displayed in the Smithsonian while the Wrights, who were enjoying considerable commercial success in Europe, sent the Wright Flyer to the Science Museum of London – where it remained for twenty years. It was finally put on display in the Smithsonian on December 17, 1948. The Langley Aerodrome was eventually displayed in the Udvar-Hazy Museum. Both machines, and their designers, rightly deserve recognition for furthering the science of aviation.