4. DR. ROBERT GODDARD

Robert Hutchings Goddard was born in Worcester, Massachusetts on October 5, 1882. His father, Nahum Goddard, was an inventor. Now, like many children, young Robert learned to generate static electricity by shuffling his feet on the carpet – his father showed him how. The electric age was beginning. Cities were getting electric lights, and the boy became fascinated with the magic of electricity. Could he charge a zinc battery by scuffing his feet on a sidewalk, enabling him to jump higher if he held on to the zinc?

His mother was frightened that he might sail away and so that experiment was called to an end by her decree. Robert Goddard’s curiosity however, was something not so easily put to rest. The young boy loved nature. He loved observing the flight of birds. He also stared for hours into a telescope given to him by his father. Though the family had moved to Boston, they often returned to the clear air of Worcester, especially after his mother developed tuberculosis.

He was a shy person, who often lost himself in nature, his telescope, his microscope, and his subscription to Scientific American. Enamored with the wonder of flight, he built kites and balloons. He even tried to build a balloon out of aluminum. There he encountered that pesky foe – weight! His notes read “Balloon will not go up, …Aluminum is too heavy. Failior (sic) crowns enterprise.”

When he was sixteen, he read H. G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, in which Britain is invaded by Martians. On October 19, 1899, the seventeen-year-old Robert was pruning a cherry tree. As he climbed to cut off dead limbs, his attention became fixed on the sky. He describes that day as follows: “On this day I climbed a tall cherry tree at the back of the barn ... and as I looked toward the fields at the east, I imagined how wonderful it would be to make some device which had even the possibility of ascending to Mars, and how it would look on a small scale, if sent up from the meadow at my feet. I have several photographs of the tree, taken since, with the little ladder I made to climb it, leaning against it. It seemed to me then that a weight whirling around a horizontal shaft, moving more rapidly above than below, could furnish lift by virtue of the greater centrifugal force at the top of the path. I was a different boy when I descended the tree from when I ascended. Existence at last seemed very purposive.”

Inspired by Samuel Langley

His ability to scale trees notwithstanding, Goddard was frail and sickly as a boy. He spent hours reading science books, then he discovered the writings of aeronautical pioneer Samuel Langley in the pages of Smithsonian. Like Leonardo centuries before him, Robert observed the subtle manner in which birds controlled their flight with movements to their tail.

He disagreed with some of Langley’s observations – largely. Because of his observations of barn swallows and chimney swifts. These little fellows were the masters of the air. He even wrote a letter to a magazine filled with his thoughts on the matter, which the magazine refused to publish. Where many young people would have been discouraged, Goddard was not. He discovered Sir Isaac Newton’s Principa Mathematica.

Well, Newton’s Third Law of Motion caught his attention; “I began to realize that there might be something after all to Newton's Laws. The Third Law was accordingly tested, both with devices suspended by rubber bands and by devices on floats, in the little brook back of the barn, and the said law was verified conclusively. It made me realize that if a way to navigate space were to be discovered, or invented, it would be the result of a knowledge of physics and mathematics.”

In 1908, Goddard graduated from the Worcester Polytechnic Institute with a degree in physics. He completed graduate work for his MA at Clark University in 1910. He received his Ph.D a year later. He continued on another year at Clark as an honorary fellow before joining Princeton University’s Palmer Physical Laboratory. He wrote a paper on “The Navigation of Space,” which he submitted to Popular Science News. It was rejected. But Goddard was fascinated with gyroscopes, and he believed they held the key to stabilizing aircraft in flight.

The Notebooks of Invention

His 1907 paper on gyroscopic stabilization of aircraft was published by Scientific American. He was now consumed with the possibilities of flight beyond our atmosphere. He filled notebooks with his ideas, not unlike the man from Vinci. Rockets were the answer! No, not the solid fuel stuff of fireworks, but liquid fueled and controllable! They would be the chariot that would take us to the heavens.

On February 2, 2, 1909 Goddard wrote a paper on liquid fueled rockets. He proposed using liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. He continued to do the math – calculating trajectory and efficiency of his spaceship. He became ill. He was running out of money, but in January of 1917, in response to his paper A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes, the Smithsonian Institute gave him a grant to continue his. Work.

Rocket research was not considered ‘real science’ by Goddard’s peers. Nonetheless, the same peers were impressed at the amount of funding he was able to secure. Worcester Polytechnic Institute even allowed Goddard to set up shop in their abandoned Magnetics Laboratory on the edge of campus. That, it was felt, would be a safe place for rocket science to be tested.

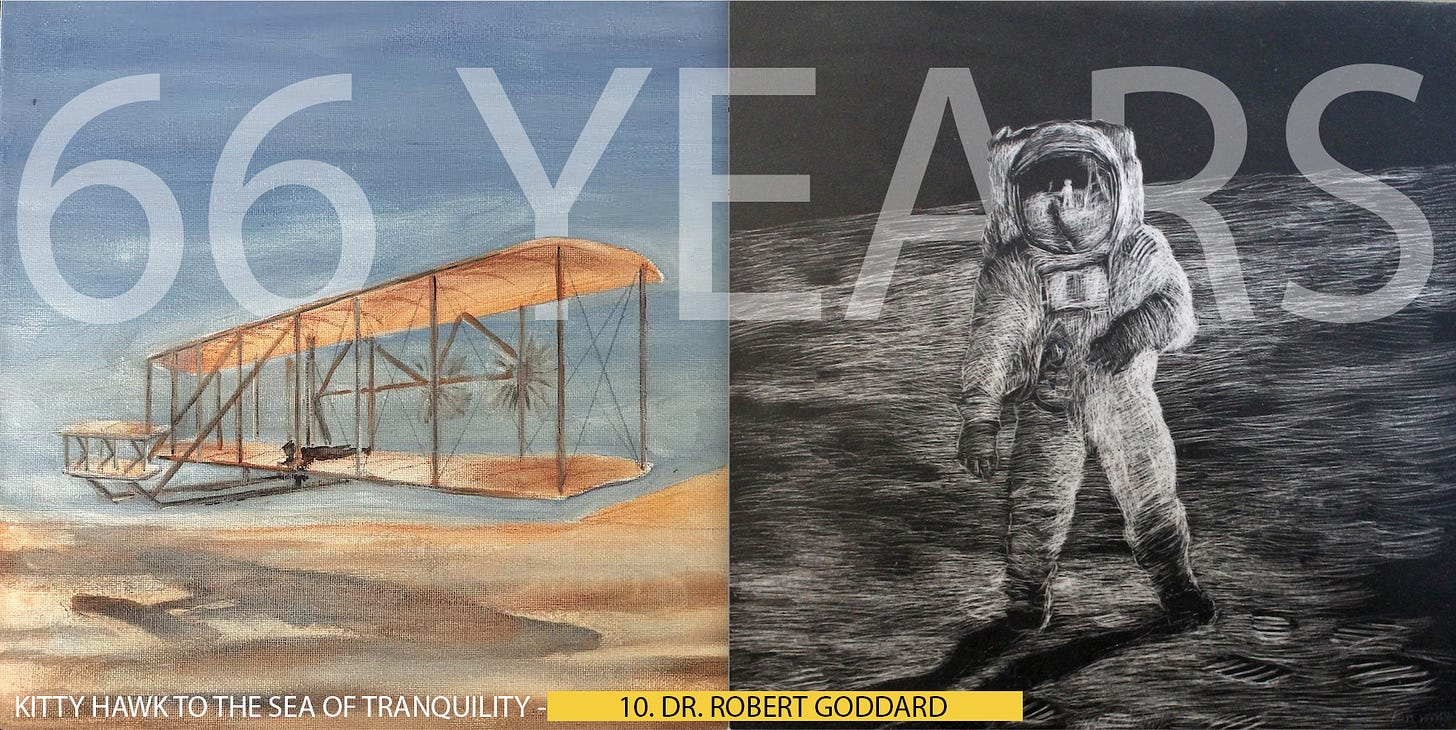

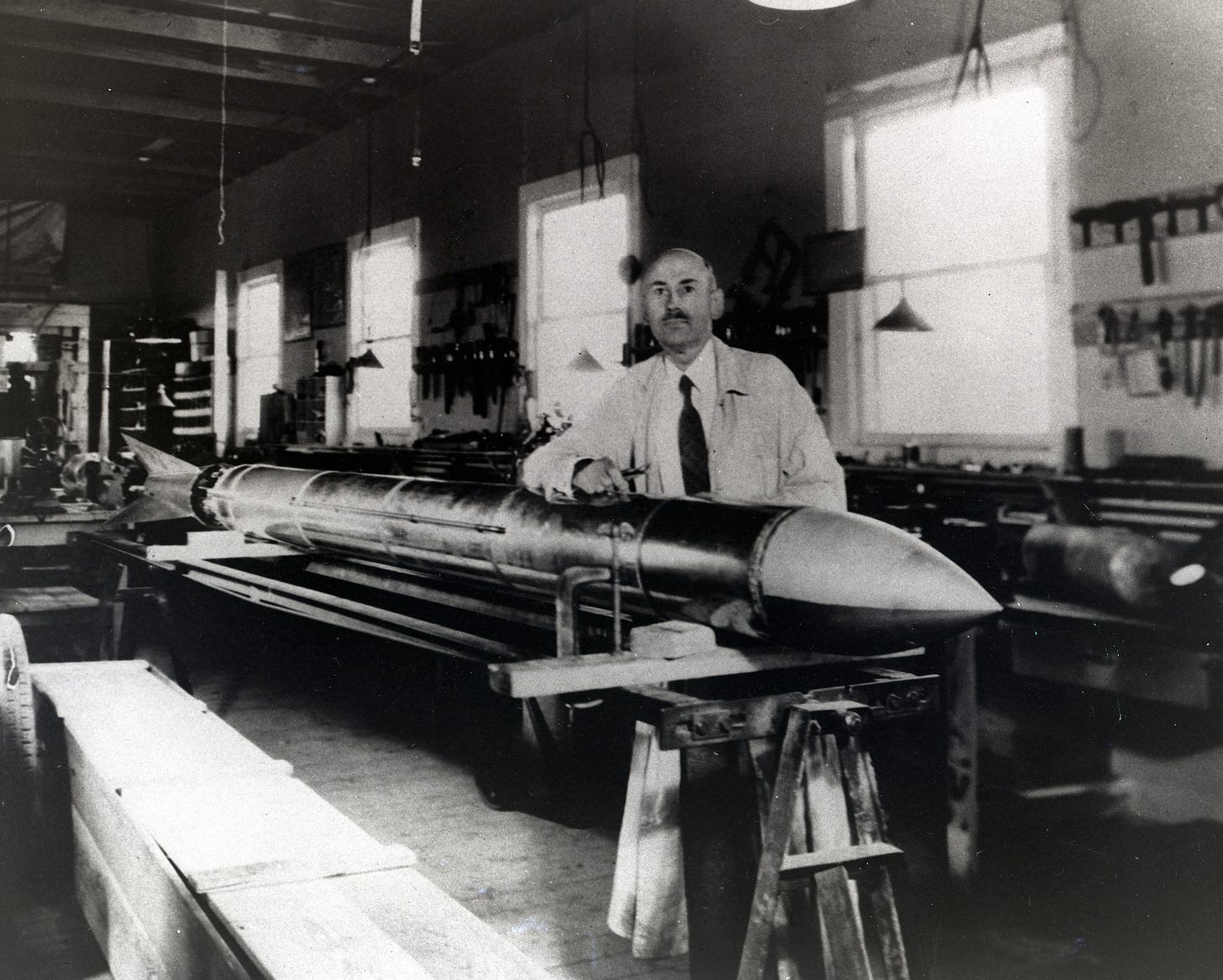

Dr. Robert Goddard in 1926 with his prototype rocket. — NASA Photo

Dr. Goddard with a rocket in his New Mexico laboratory. — NASA Photo

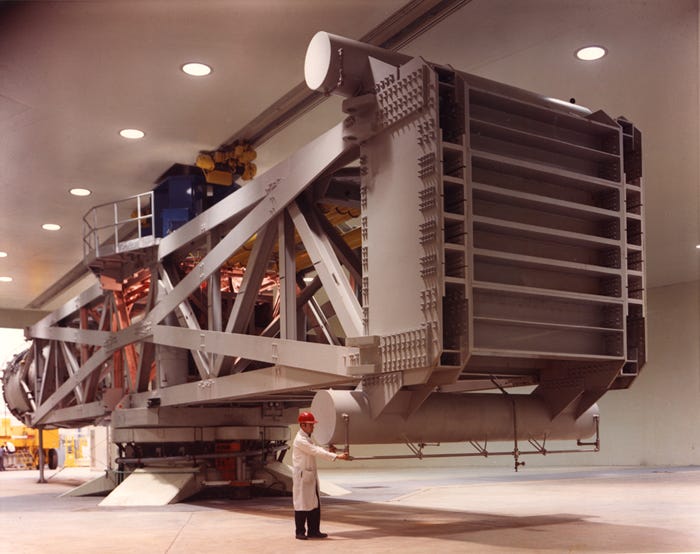

Goddard Space Flight Center’s Launch Phase Simulator. — NASA Photo

In 1920, Goddard published his research on high altitude rocket research – speculating on the possibility of reaching the moon. He was ridiculed by the press and distained by his peers. But his work did not go unnoticed in Europe. In 1927 the German Rocket Society was established. The German military would begin its rocket program in 1931. Also in 1931, Russian/Ukrainian aviation enthusiast Sergei Korolov and his partner Friedrich Zander created the GIRD Jet Propulsion Study Group, which would become a research and design laboratory developing rocket aircraft.

On March 16, 1926 the space age began as Goddard launched his first liquid fueled rocket. The man who had once almost blown up his parents’ house, and his university laboratory, was now sending his rockets skyward. His neighbors in Worcester were not thrilled with this and so Goddard was forced to continue his tests in New Mexico.

Recognized posthumously as the father of modern rocketry, NASA named its Goddard Space Flight Center after him in 1959 – and Dr. Robert Goddard would have loved it. Here engineers tackled the weighty problems of flying in space. Here my father, Ed Kirchman, would design and build a device called the Launch Phase Simulator (pictured above) to study the forces of vibration, acceleration, vacuum, and the extreme heat and cold that spaceflight would subject a rocket and its payload to.

Goddard, in that time, was recognized as a pioneer of rocket science and the practical application of physics necessary for it to happen. In 1966 he was inducted into the International Aerospace Hall of Fame and the National Aviation Hall of Fame. In 1976 he was inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame.