“Cyclopes,” Acrylic on Paper, 11” x 8 1/2” by Bob Kirchman

Yesterday morning this was a demonstration painting I did for our students. After visiting the Cyclopean Towers (Natural Chimneys) of Augusta County, Virginia, Polyphemus must have been on my mind — especially when you consider the very interesting shadow I noticed at the stone towers.

“Shadow of Polyphemus” — Photo by Bob Kirchman

The Cyclopes, to whom the ancients attributed the Mycenaean stonework, became the legendary builders of the Cyclopean Towers of Augusta County, Virginia.

A great project to connect America from coast to coast would also assume legendary status.

“Cyclopean Stonework,” Greece, Mycenae, cyclopean masonry, backside of the Lion's gate. — Berthold Werner

“A Work of Giants”

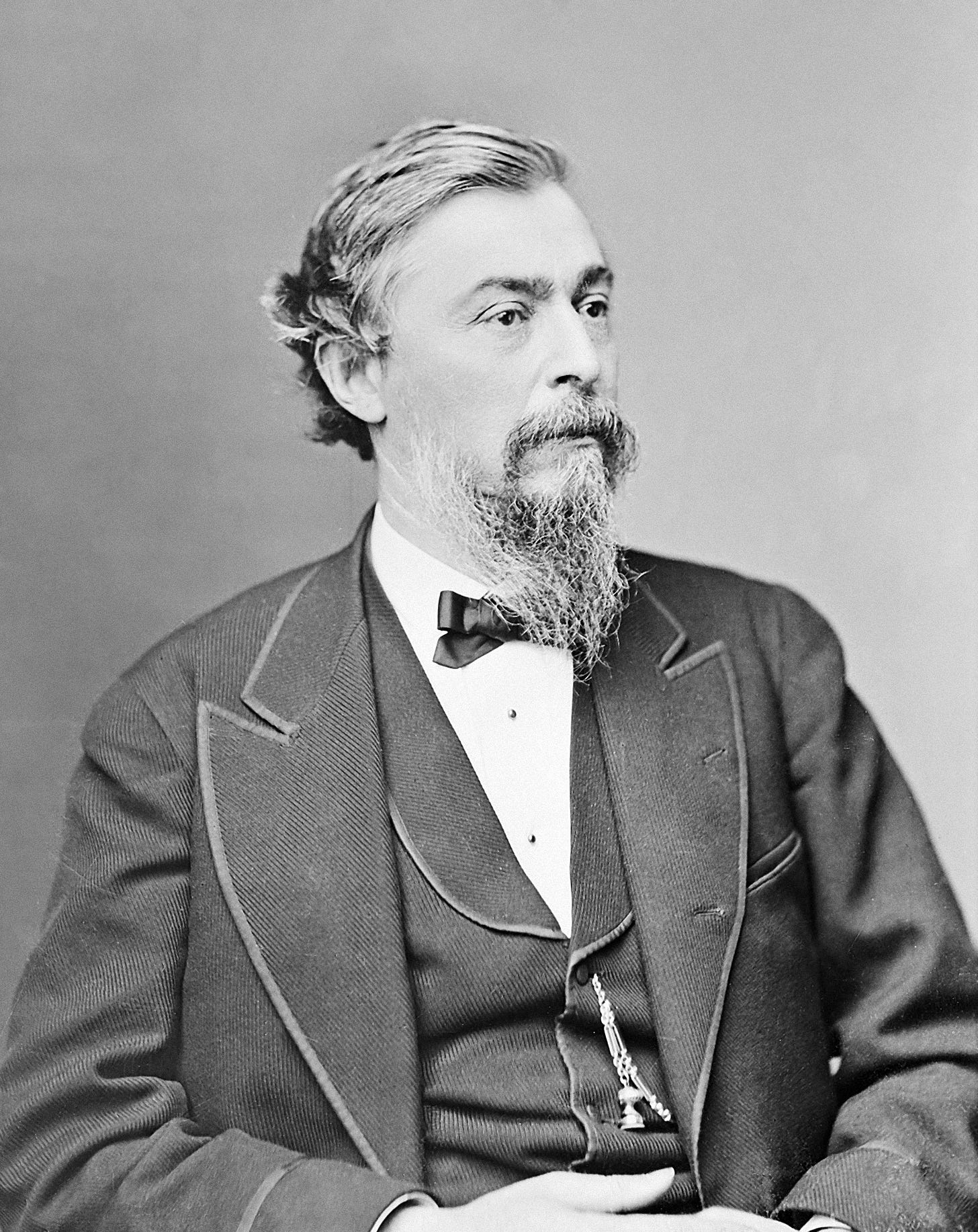

Thomas C. Durant — Photo by Mathew Brady

A Different Sort of “Giant” Built American Railroads

In the early 1860’s there were two Americas. There were the Eastern states who would all too soon divide into Union and Confederacy, but then there was California. Although America stretched from “sea to shining sea,” California was isolated from the East by what many considered miles of uninhabitable desert. To get to California, one often took passage on a ship to Panama, made a short trip overland and then boarded another ship for San Francisco. California, in time, could have easily become another country.

Then there was the great settlement of the Latter Day Saints at Salt Lake. There could have been another nation created by their isolation on both sides. Railroads were already well established in the East, but there was none crossing the great desert. Hearty pioneers walked beside their ox-drawn wagons on trails to California and Oregon, but they likely saw this as a one-time migration, never looking back. Commerce was not possible on any scale without improved transportation.

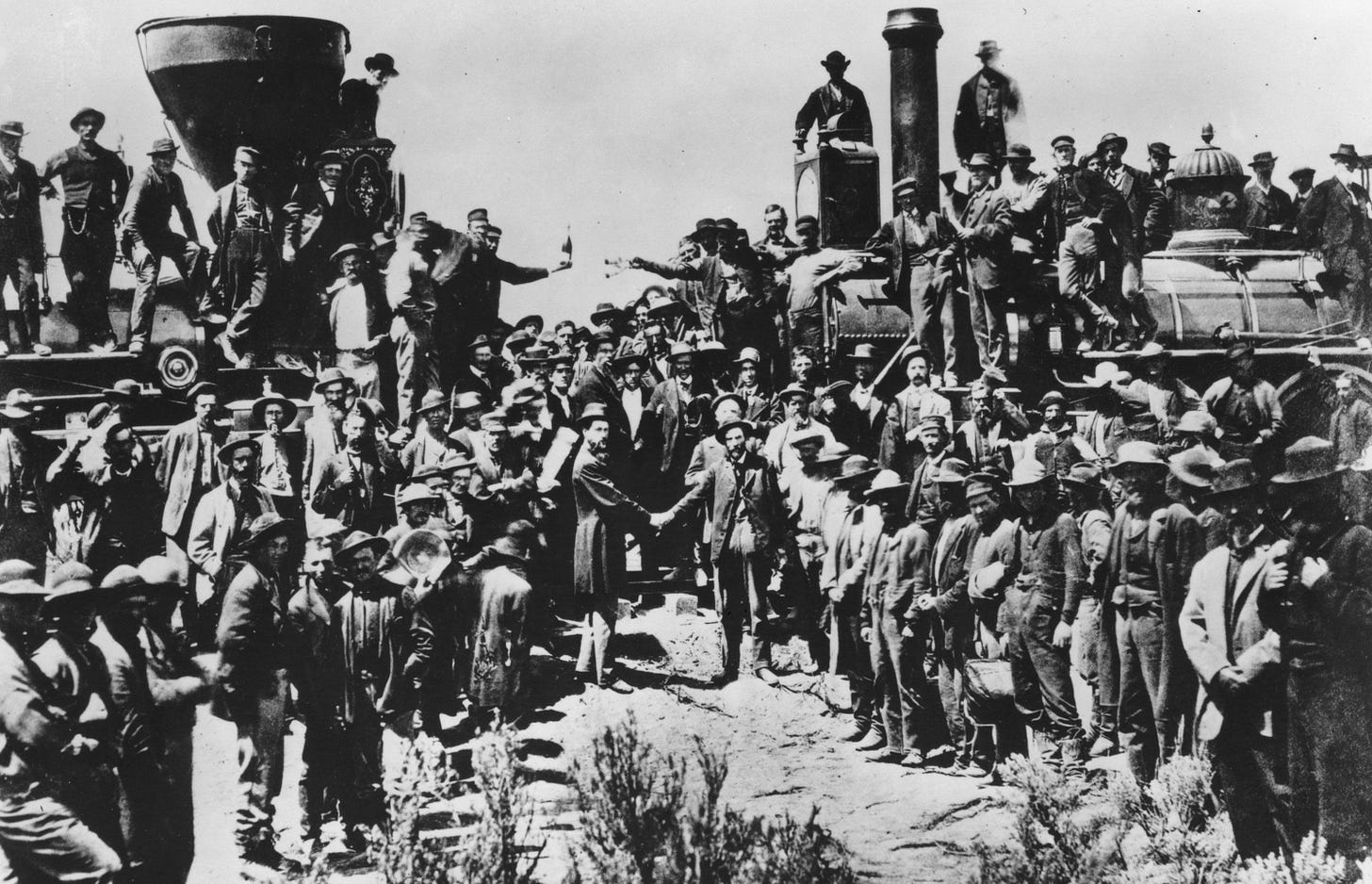

As the Nation advanced toward her terrible Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln signed The Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 that made construction of the transcontinental railroad possible. It assigned the job to two companies: the Central Pacific Railroad of California was to build eastward from Sacramento, and a new company called the Union Pacific was to build westward up the Platte River Valley from Omaha, Nebraska. It was called a “work of giants” by some, but if they were giants, there were some of them who were not unlike the ruthless Philistine: Goliath.

The greatest ‘Goliath’ of all, in the building of the Union Pacific road would have to be Dr. Thomas Clark Durant. Trained in medicine, he kept the title as he pursued schemes for making money. He founded a railroad company, the Missouri and Mississippi Railroad, in 1854. Though he built very little of it, he poised himself to take advantage of a future Pacific railroad project, should it come to be. During the Civil War, he and his associate Grenville Dodge smuggled contraband cotton out of the South. With the money he made from smuggling, he invested in a fairly devious subscription scheme that left him in control of the Union Pacific Railroad Company.

Now the good doctor made himself Vice President and named a figurehead President for the company. Dodge would become his chief engineer. As the road was built, the scheming Durant would come into conflict with Dodge, as the engineer fought to direct resources to building track and Durant tried to divert them.

Prior to the Civil War the building of the road had been stalled by a dispute over whether a Northern or Southern route should be chosen. Secession allowed for the decisive selection of the Northern route from Omaha. The Pacific Railroad Act of 1862 had set aside a land grant to finance construction, but in the Civil War era it was not enough. The Pacific Railroad Act of 1864 increased the incentives.

Oakes and Oliver Ames had made a lot of money making shovels during the gold rush. They graduated to providing cannon during the war. The brothers put up a million dollars of their own money and pledged their credit to get the road built. By the end of 1965, however, Thomas Durant had spent half a million dollars and had laid only 40 miles of track across Nebraska. Grenville Dodge had a reputation, gained during the war, for building (and rebuilding) railroads with great speed. Durant appointed him chief engineer of the project. The conflict between Dodge and Durant as the road progressed would become legend, but Dodge was the man to get the job done. In a letter to his brother, Dodge speculated that he would likely have trouble with Durant. The two had worked together before and Dodge’s fears were well founded.

By 1866 things had changed. A newspaper man wrote: "The track laying on the Union Pacific was a science. We, pundits of the far East, stood upon that embankment, only about a thousand miles this side of sunset, and backed westward before that hurrying corps of sturdy operators with a mingled feeling of amusement, curiosity and profound respect. On they came. A light car, drawn by a single horse, gallops up to the front with its load of rails. Two men seize the end of a rail and start forward, the rest of the gang taking hold by twos, until it is clear of the car. They come forward at a run. At the word of command the rail is dropped in its place, right side up with care, while the same process goes on at the other side of the car.

Less than thirty seconds to a rail, and so four rails go down to the minute. The moment the car is empty it is tipped over on the side of the track to let the next loaded car pass it, and then it is tipped back again, and it is a sight to see it go flying back for another load, propelled by a horse at full gallop at the end of sixty or eighty feet of rope. Close behind the first gang come the gaugers, spikers and bolters, and a lively time they make of it. It is a grand 'Anvil Chorus' that those sturdy sledges are playing across the plains. It is in triple time, three strokes to the spike. . .ten spikes to a rail, four hundred rails to a mile, eighteen hundred miles to San Francisco. Twenty-one million times are those sledges to be swung ... before the great work of modern America is complete."

In Salt Lake City, which had been established two decades before the railroad came, Brigham Young was not happy. The shortest route for the new railroad had been laid across the Northern shore of the Great Salt Lake. Salt Lake City was on the Southern end of the lake. The rails would meet on the deserted Northern side of the lake at Promontory in 1969, but a spur would need to be built to serve Salt Lake City. Though he was not pleased with this arrangement, the Mormon leader still took a grading contract for the Union Pacific and one of his bishops took one with the Central Pacific.

Then there was no harmony at Promontory as the two lines built past each other, grading out parallel roadbeds. Grading crews would set off charges without warning to harass the men working on the grade beside them. It literally took an act of Congress to settle the joining point would be at Promontory. Durant, for his part, had not been paying his men. The men revolted, kidnapping Durant and chaining his private car to the tracks. Durant wired to his board of directors for $500,000 to pay the men and arrived late for the ceremony at Promontory.

Grenville Dodge and Durant’s relationship was frayed beyond repair. After the lines joined at Promontory, Oliver and Oakes Ames made plans to oust the scheming Durant, but he resigned before they could fire him.

David McCulloch adds this, perhaps greater perspective: "In the same year the road was completed, 1869, another monumental epic engineering feat was completed; the Suez Canal. Suddenly the world was getting smaller, an idea that inspired Jules Verne to write 'Around the World in Eighty Days.'" The great work of Nineteenth Century America had been built by men who were less than giants, men with feet of clay, but build it they did.

In the wake of America’s horrible Civil War, revival had begun. Ferenc Morton Szasz writes:

Though such signs of spiritual life appeared all over the Western landscape, they are completely absent from most people's visions of the nineteenth-century American frontier. Names like Buffalo Bill, Sitting Bull, Annie Oakley, Calamity Jane, Billy the Kid, and Wyatt Earp are almost synonymous with the West, while names like William D. Bloys, Daniel S. Tuttle, Charles Sheldon, Sheldon Jackson, and Brother Van Orsdel ring few bells. Yet if one looks at actual accomplishments, the situation might well be reversed. Most Western communities owe far more to these unheralded clerics than they do to the high-profile outlaws or icons.

From about 1840 to the end of the century, these largely anonymous ministers shaped the contours of Western life in three major ways. They formed the first churches and Sunday schools, which promoted social stability while reining in local violence; they developed a distinctly Western style of Christianity that emphasized a non-denominational message of salvation and personal ethics; and they helped lay the institutional foundations - orphanages, hospitals, and schools - for scores of Western communities.”

Though the railroads had been built by speculators and schemers, it was the great message of the Gospel that laid the foundations for the society of America’s vast interior.